Appointment of Judges and Independence of the Judiciary is very closely related. In Indian Constitution, Supreme Court Judges are appointed by the President after consultation with CJI and other senior judges. Much has been in the news about the appointment of judges for past some years. In India, the constitution has provided for the appointment of Judges of Supreme Court and the High Courts under articles 124(2) and 217 respectively.

- “Article 124 (2) deals with the appointment of Supreme Court judges. It says: “Every Judge of the Supreme Court shall be appointed by the President by warrant under his hand and seal after consultation with such of the Judges of the Supreme Court and of the High Courts in the States as the President may deem necessary for the purpose and shall hold office until he attains the age of sixty-five years. Provided that in the case of appointment of a Judge other than the Chief Justice, the Chief Justice of India shall always be consulted.”

- “Article 217 deals with the appointment of High Court judges. It says: “Every Judge of a High Court shall be appointed by the President by warrant under his hand and seal after consultation with the Chief Justice of India, the Governor of the State, and, in the case of appointment of a Judge other than the Chief Justice, the Chief Justice of the High Court.”

No where in the provisions of the Constitution has the collegium system been mentioned. But the Collegium system is a result of the Supreme court’s series of judgments to decide the appointment of judges in the higher judiciary. When the constitution came into force, the practice was that the senior-most judge was appointed as the Chief Justice of India. And as far as appointments of other judges of Supreme Court and high courts were concerned, the President would appoint them in consultation with the Chief Justice of India and such other judges of the Supreme Court and the High Courts as he deemed necessary.

It was an uncontroversial process, until Kesavananda Bharti case, where after the three senior judges who pronounced the judgement were superseded and Justice A N Ray was appointed as the CJI by the then President. This results in the three senior-most judges resigning from their posts because they were not looked upon by the government of that day as they had pronounced a judgement which was not favourable to the then government. Thus, there was commencement of controversies with regards to appointment of judges.

However, upon appointment of A N Ray as CJI was followed in succession with a series of favouritism saga, which was described as steps to curtail the independence of judiciary. This favouritism saga included transferring of the judges who did not comply with the government’s will and wishes. Also there were appointments of additional judges in the high courts. In a series of events, in 1981, a circular was issued by the then Union Minister for law and justice, through which directions were issued to the Chief Ministers of the states to seek names of the additional judges of the respective high courts along with order of preferences to be transferred and made permanent judges of any high courts in India.

This was a clear executive interference in the appointment and transfer of Judges. The constitutional validity of the circular was challenged by a series of writ petitions, which also challenged the practice of appointing additional Judges and the transfer of Judges from one state High Court to another. The Supreme Court heard this matter which came to be known as First Judges Case.

First Judge Case:

“Consultation vs. Concurrence”

The S P Gupta vs. Union of India (1981) is called the “First Judges Case”. It declared that the “primacy” of the CJI’s recommendation to the President can be refused for “cogent reasons”. The Supreme Court bench held that the word ‘consultation’ which is used in the Article 124 and 217 was not ‘concurrence’. In simple terms, it mean that although the President will consult with these functionaries, his decision was not be bound to be in concurrence with all of them in any manner. Thus, in case of disagreement, the ultimate power would be the Union Government and not the CJI. This brought a paradigm shift in favour of the executive having primacy over the judiciary in judicial appointments for the next 12 years until 1993.

Second Judges Case:

The opportunity to restore the balance came with the Second Judges Case. In the late 1980s, a series of petitions were led before the Supreme Court asking for various vacancies of Judges to be led in the Supreme Court and High Courts.

The Supreme Court Advocates on Record Association vs. Union of India (1993) came to be known as the “Second Judges Case”. In this case, the judgement that was given by the 9-Judges Bench over-ruled the judgement in the case of S.P.Gupta vs. Union of India saying “the role of the CJI is primal in nature because this being a topic within the judicial family, the executive cannot have an equal say in the matter.” The court held that in the event of disagreement, it is the CJI whose opinion would not only me primal but also determinative. Adding checks and balances, the court further held that the powers of the Chief Justice of India would be moderated by a Collegium System, where, for appointments to the Supreme Court and High Courts, the Chief Justice of India would decide after ascertaining the opinion of two of the most senior Judges of the Supreme Court. Similarly, for the appointment of High Court Judges, the Chief Justice of the High Court would make recommendations only after ascertaining the opinion of two of the most senior Judges of the High Court.

The judges today are selected through the collegium system only. The collegium system has its genesis in a series of three judgments that is now clubbed together as the “Three Judges Cases”. Over the course of these cases, the court has evolved the concept of judicial independence, which means that except judiciary no other organ of the government including the legislature and the executive shall have any say in the appointment of the judges.

To understand what is the judges case, it is important to understand the collegium system first. What exactly is this system and how it functions is mentioned as below:

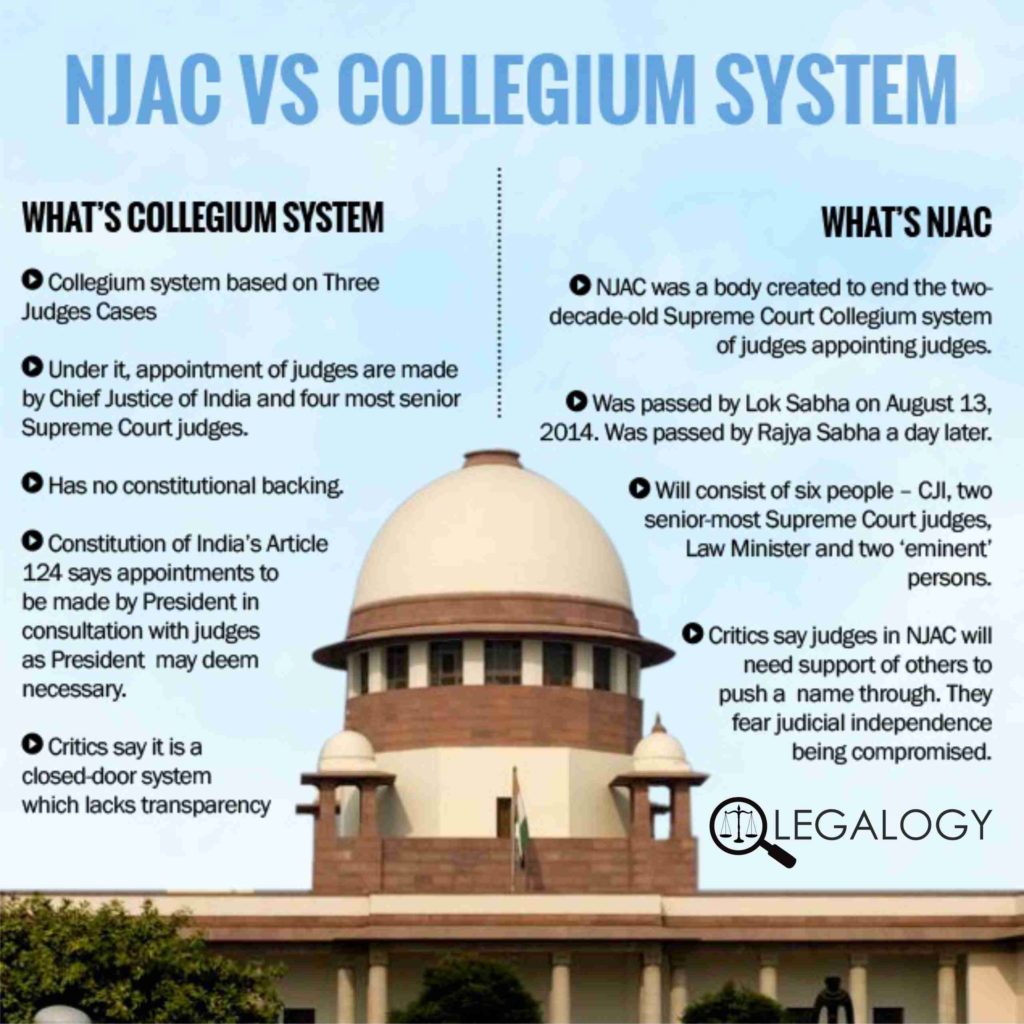

- “It is a system under which appointments and transfers of judges are decided by a forum of the Chief Justice of India and the four senior-most judges of the Supreme Court.” This in simple terms means that this is a system in which the judges are appointed and transferred by the judges only.

- This system evolved as a result of series of judgements of Supreme Court and not by any act made by parliament and it also does not have provision in the Indian Constitution.

- The Supreme Court collegium is headed by the CJI and consists of 4 senior-most judges of the court along with the CJI.

- Similarly, High Court collegium is led by the Chief Justice of that High court and 4 senior-most judges of the court.

Third Judges Case:

This is not a case per se; but it is an opinion delivered by the Supreme Court, responding to a question of law regarding the collegium system of appointing the judges. In 1998, President K R Narayanan issued a Presidential Reference to the Supreme Court over the meaning of the term “consultation” under Article 143 of the Constitution (advisory jurisdiction). The question of law here was whether ‘consultation’ required the consultation with the number of judges in forming the opinion of the CJI’s opinion; or whether the sole opinion of the CJI would constitute a consultation. The Supreme Court in response to this laid down 9 guidelines for the appointment and transfer of the judges of higher judiciary — this has come to be the present form of the collegium, and has been prevalent ever since. This opinion laid down that the recommendation should be made by the CJI and his four senior-most colleagues, instead of two. It also held that Supreme Court judges who hailed from the High Court for which the proposed name came, should also be consulted. It was also held that even if two judges gave an adverse opinion, the CJI should not send the recommendation to the government.

Role of Government under the Collegium System:

Coming back to the collegium system, the role of government under this system is very limited as the judges of the higher judiciary are appointed only by the collegium system. The government’s role is limited to getting an inquiry conducted by the Intelligence Bureau (IB) if a lawyer is to be elevated as a judge in a High Court or the Supreme Court. The government can raise objection and seek clarification over the appointee name proposed by the collegium before appointment. But, if the collegium reiterates the same appointee name as proposed earlier, the government becomes bound under previous constitutional bench judgements to appoint that appointee as a judge.

Also, when the High Court Judges are to be appointed, the names that are recommend, reach the government only after the the approval from CJI and Supreme Court collegium. This means that High Court judges can be approved by the government only once they are approved by the Supreme Court collegium and the CJI.

Short comings of Collegium System

The collegium system has been criticised because of its non transparent workings. It is seen as a closed-door affair with no prescribed norms regarding eligibility criteria or even the selection procedure. There is no public knowledge of how and when a collegium meets, and how it takes its decisions. Lawyers too are usually in the dark on whether their names have been considered for elevation as a judge. Another limitation of the collegium’s field of choice to the senior-most judges from the High Court for appointments to the Supreme Court is that overlooks several talented junior judges and advocates. Many are of the view that the collegium is autocratic in nature ans there is no mention of such system in the constitution. It encourages mediocrity in judiciary and more over it promotes nepotism because sons and nephews of previous judges or senior lawyers tend to be popular choices.

National Judicial Appointments Commission

The Constitution (Ninety-Ninth Amendment) Act, 2014, replaced the Collegium system with the National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC) in the context of mounting criticism over lack of transparency and accountability in judicial appointments. This Amendment and the NJAC Act, 2014, which received assent of the President in December 2014, provided that the appointment to higher judiciary would be now by way of a commission comprising of:

- The Chief Justice of India as the Chairperson,

- Two other senior Judges of the Supreme Court next to the Chief Justice of India as Members,

- The Union Minister in charge of Law and Justice as Member,

- Two eminent persons to be nominated by the committee consisting of the Prime Minister, the Chief Justice of India and the Leader of Opposition in the House of the People or where there is no such Leader of Opposition, then the Leader of the single largest Opposition Party in the House of the People, as members. One of the eminent persons shall be nominated from amongst those belonging to the Scheduled Castes, the Scheduled Tribes, Other Backward Classes, Minorities or Women.

The NJAC Act, 2014, provided that if any two persons of the Commission did not agree with a nomination, the NJAC would not recommend such candidate for appointment. Hence, judicial appointments ceased to be the primacy of either the executive or the judiciary and civil society’s participation was now included in the process of appointment.

Fourth Judges Case

Within days of the Ninety-Ninth Constitutional amendment and NJAC Act, 2014, coming into force, the constitutional validity of both the Ninety-Ninth Constitutional amendment as well as the NJAC Act, 2014, was challenged. A constitutional bench of 5 Judges struck down the Ninety-Ninth Constitutional Amendment Act and consequently the NJAC Act, thereby declaring the said amendment as unconstitutional. The Bench sealed the fate of the proposed system with a 4:1 majority verdict that held that judges’ appointments shall continue to be made by the collegium system in which the CJI will have “the last word”. “There is no question of accepting an alternative procedure, which does not ensure primacy of the judiciary in the matter of selection and appointment of judges to the higher judiciary,” said the majority opinion.

Though NJAC Act, 2014, was struck down as unconstitutional, the Supreme Court in the course of the hearing, recognised and acknowledged that the Collegium System as it existed, had its own shortcomings. Therefore, the Supreme Court called for suggestions both from legal fraternity and civil society to evolve a more transparent and accountable system of judicial appointments. The Bench had asked the government to draft a new Memorandum of Procedure after consultation with the CJI.

But more than a year later, the MoP is still to be finalised owing to lack of consensus on several fronts between the judiciary and the government. There has been a state of standoff between the Collegium and the executive in regard to making the new MoP. This resulted in several delays in appointments to the higher judiciary despite rising vacancies. The Central Government circulated a draft MoP that was met with stiff resistance by the Collegium, without whose approval the CJI could not assent to the same. However, after having been negotiated several times over, recent reports in 2017 indicated that the fate of new MOP had been resolved. Some of the resolved issues include a clause that allows the Central Government to reject a candidate’s appointment on grounds of national security, and the setting up of secretariats in the High Courts and the Supreme Court to maintain a database of Judges that aid the Collegium in the selection process.

Conclusion

The former Finance Minister Late Arun Jaitley had questioned the exclusivity of the judges appointing the judges, saying “ the collegium system was akin to the Gymkhana Club here where members appoint the future members.” As for the case regarding the collegium system, the opinion still stands divided about the desirability of judicial activism. Most agree that it is the judiciary and its fearless will to intervene and deliver justice, even at the risk of stepping into the domain of the legislature or the executive, which has preserved democratic process over the years. Simultaneously many believe that it is not only that the independence of judiciary is important, but the credibility is also important.

Click Here to read our article on Judicial Accountability in India